Anthony A. “Tony” Williams: the ties that bind

From stand-up comedy in LA to mayor of the world's most consequential city

America has had its share of charismatic politicians, from “The Kingfish” Huey Long and “Fighting Bob” La Follette to rough-riding Teddy Roosevelt and fiery Marion Barry.

No one has ever described Anthony A. “Tony” Williams as charismatic.

I was introduced to Tony by my former law school classmate and friend, Eric Lindner. As a D.C. native who at one time ran a Washington-based company that employed 2,000 and had frequent dealings with the City government, Eric obviously knew of Tony when he was Mayor of The District of Columbia. However, when they met in 2022, while Tony said they’d met before, Eric couldn’t recall, which is a clue to the sort of person Tony is: really smart, really focused and really self-effacing. They laughed about their respective memories and reverse migratory patterns, in that Tony was born in California, and now lives in D.C., whereas Eric was born in D.C., and now lives in California. Eric: “I guess I didn’t get the memo about how everyone was leaving California.” Tony: “Guess not.”

I did get the memo: my husband and I left Oakland for San Antonio in 2019. As I follow national politics very closely, my time at Yale overlapped with Tony’s, our fathers were both very successful—and very rare—Black officers in the U.S. military, my father ran for office in Chicago, and Tony was a sign of hope for another city I dearly loved—when Eric asked if I might like to write a profile of Tony, I was all in.

I lived in D.C. from 1980-1982, until the U.S. Senator I worked for as a Research Assistant got swept out in the Reagan wave of 1980 (my boss’s having supported the nomination of Alabama’s first Black federal judge didn’t help). I remember the Marion Barry saga very well, the chaos as well as the accomplishments. The soft-spoken, bowtie-wearing self-professed bean-counter Tony is perhaps best-known as Felix to Barry’s Oscar in the Odd Couple that once ran D.C.; or rather part of it, the part not controlled by the federal government. Barry was a brash and brilliant paradox: he marched peacefully with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. yet also incessantly provoked the White Congressional political establishment. When it suited his purpose, he called out the ex-Dixiecrats, ex-Klansmen and former Rizzo machine operatives who, though they'd once sided with George Wallace and Jim Crow to block Voting Rights, had managed to move into leadership positions in the Democrat Party. Barry said leopards rarely changed their spots. His rhetoric was catchy: he’d call his allies little more than Slave-masters in Brooks Brothers suits. His willingness to speak truth to power often endeared him to Black Washingtonians, but his habit of continually biting the hand that fed D.C.’s residents (Uncle Sam, though Barry often preferred Uncle Tom) wore thin, and he lacked the personal discipline to enact and/or administer the sorts of programs that could really help the people he claimed and wished to serve.

When the showman side of Mayor Barry finally got the better of him, D.C. crashed and burned, according to almost every key metric: crime ran rampant, businesses, law firms and associations fled for Virginia or other States, and the trash piled up like in Nice during a hot summer strike. In 1995, Barry appointed Tony as DC’s independent Chief Financial Officer. Once approved by the Financial Control Board, he began working with and on behalf of local officials, the Board, and the U.S. Congress.

Most people wrote him off. But not canny Democrat President Bill Clinton, very conservative GOP Senator Sam Brownback, or anyone else who’d come to know Tony over the years, including his former teachers and classmates at LA’s Loyola High School, fellow cadets at the Air Force Academy, the Vietnam vets and blind orphans he helped as a volunteer, and his former municipal, state and federal government colleagues in places as diverse as Connecticut, Missouri, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (where he was the first CFO; nominated by Clinton, and confirmed by the Senate). “People always underestimated Tony,” said a longtime friend. “People often bet against him, and always lost their proverbial shirt.”

Tony orchestrated one of the most stunning turnarounds by any American chief executive since WWII. Despite his very limited control of the levers of power, in less than two years, he converted a $355 operating deficit into a $185 million profit, while vastly improving the quality of City services.

Soon even the founding members of The Marion Barry Fan Club were singing Tony’s praises. He was someone who put the lie to the idea that Black politicians are all “style and profile,” but can’t run a major city. No longer did D.C.’s residents just want rhetoric. They were tired of the sizzle; having been burned by it, they hungered for steak. Wanting competence, they drafted a reluctant Tony to run for D.C. Mayor, then voted him in, replacing his mentor, Marion Barry.

Working even more closely with all of the stakeholders, from the wealthiest citizens of Ward 2 to the poorest in Ward 8, from the one who resided at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue to the 435 who worked on Capitol Hill, Tony crafted a compelling vision, drew up a comprehensive plan, and led the process of rigorous implementation by role-modeling, coaching, and facilitating the transformation to a bright future. D.C. went from laughingstock to world class city, according to numerous objective rankings. He brought in billions in investment (much of it from overseas) and reversed the exodus of taxpayers. Governing magazine hailed Tony as “America’s best public servant,” owing to his masterful navigation of “the complicated, brutal, Byzantine political environment of Washington, D.C.,” while MSNBC called him “one of the best mayors in American history.”

When I asked Tony “How did you do it?” he responded, “Thanks to a lot of great people, all working together.” When I pressed: “But surely it was your leadership that harnessed and galvanized these people”—he looked uncomfortable, shifted in his chair, and mumbled something inaudible. I said, “Excuse me?”

My attempt to elicit anything that even hinted of self-aggrandizement fell on deaf ears. Tony always chalks it up to “good fortune” or lauds others. If somehow the results reflect well on him, well, he’s the last person to say so.

However, I eventually pried out Tony’s "Code of Conduct.” Though this is my term, he agrees to its contents. He says he learned nine lessons early in life, and they have stood the test of time for 70-plus years.

1. Humility is always the best policy.

“I’m the modest sort,” he says. “I am who I am.” Who he is, is the Poster Child for what leadership guru Marilyn Gist says is the common denominator and cardinal virtue of the world’s best leaders: humility. This wisdom is as old as St. Augustine, which was drilled into me as a kid in school, in Chicago: “The sufficiency of my merit is to know that my merit is not sufficient.” Humility and modesty at the top trickle down to engender motivation throughout the ranks. Lower-level staffers know that even their “crazy ideas” won’t be laughed at, and that it’s okay to make mistakes. “As I’ve made on many occasions,” Tony is quick to point out.

As for his former mentor, Tony said “I would never trash Marion. The African-American community understood where we both stood in the arc of history. He was a good mayor, and helped create an African-American middle class. He did a lot of great things. And then he didn’t. That’s where I came in.”

2. Listen.

Tony has always been a leader, starting in grade school. When asked what advice he would give to young leaders, especially Black leaders, Tony responded, “Listen. Read everything. Take input from everyone, regardless of what their position may be. There are two types of leaders: fierce, vocal, upfront, like, for example, Malcom X. And there are other leaders who are much more about listening to others in order to perceive points of commonality, and then build off of them to negotiate and broker deals, like Martin Luther King. You’re always balancing the here and now versus the vision. Most of the work is going to get done by the people who are focusing on the tactical not just the strategic, and when it comes to tactics, listening is vital.”

3. You don’t command respect with words, you command respect with actions.

In certain ways, Tony’s father was the most powerful force in his life growing up. That isn’t a surprise given the fact that Lewis Isaac Williams III rose to the rank of Captain in the U.S. Army during WWII, when Black officers were unicorns. According to Tony, “he’d been awarded two, maybe three Bronze Stars, which probably equated to Silver Stars and maybe even a Medal of Honor, as the African-American soldiers typically had to do twice as much to earn the same medals as White soldiers.” He says this with no rancor, more in the manner of a resigned research anthropologist, one who has studied the subtle ways of American racism for decades. Capt. Williams commanded deep respect in his job as a supervisor at LA’s West Adams post office, at home, and everywhere else in between. “He was really tough but he was fair.”

Tony and I shared our experiences in that his father and my paternal grandfather were both highly educated men relegated to work at a U.S. Post Office, one of the few non-discriminatory workplaces that provided some opportunities for advancement for Blacks. In a refrain all too common in Black America, our ancestors knew it wasn’t fair but they soldiered on uncomplainingly in order to take care of themselves and uplift their children. We also share a bond in having been raised by two strong Black parents, both of whom demanded excellence. The expectations of our mothers and fathers were clear about what you were to do, and not do.

4. Use humor.

Tony surprised me: he is a very funny guy. He tells how, as a scrawny kid, he learned early to use humor to command respect and dissipate tensions. “When I grew up, I was always elected the class leader. But I was also always the class comedian. During my stump speeches, I would stand on the loading dock in high school and give funny commentary on the school, things like that. Kinda smart-alecky. Comedy was my way to connect with people. In grade school, I got beat up several times because I went a little bit too far.”

Tony and I talked about how humor puts people at ease. He noted, “Abraham Lincoln would tell funny stories to keep everyone calm and focused. I always have one-liners to throw in.” Tony taps into the long tradition of Blacks using humor to deflect and cope with racism. “Dick Gregory was a big inspiration. He said, ‘You can’t get hurt jumping out of a basement’.” Tony insightfully noted how humor is or at least can be another form of humility.

5. Music is a great leadership tool.

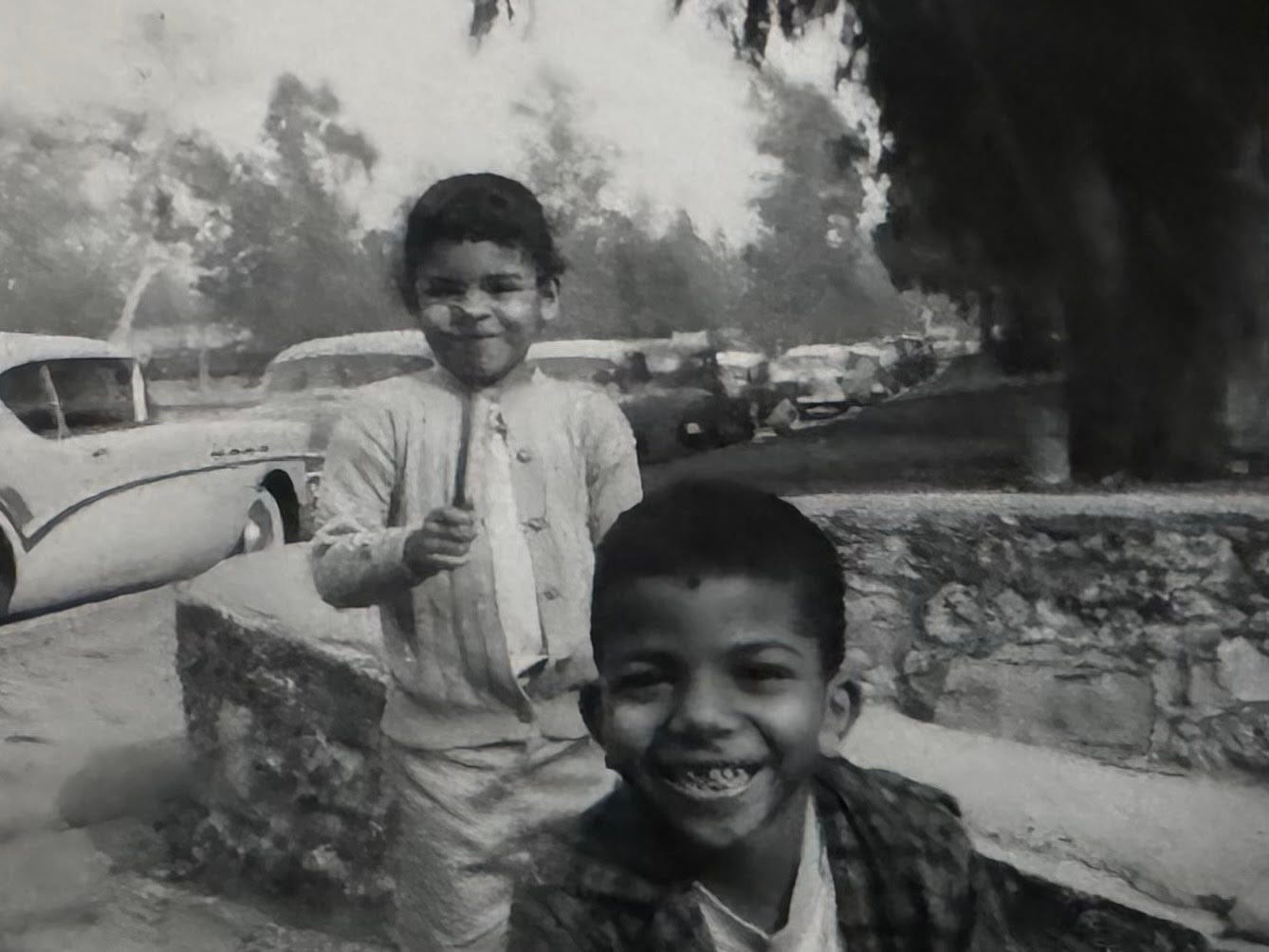

Tony’s mother also played a big role in his leadership formation. For starters, if Virginia Hayes had not been such a terrific singer, in such demand at weddings, bar mitzvahs, etc., then she and Lewis could never have afforded to adopt eight children. “And not just adopt,” Tony adds. “We lacked for nothing—materially, educationally, artistically. Mom had an amazing voice. She was larger than life. She’d be in the middle of something—cooking, vacuuming, strolling down the street, and she’d just break out singing. It was literally Singing in the Rain stuff. Sometimes a Negro spiritual in the Baptist tradition, though we were raised Catholic. But it was often opera. The way these days Black kids in LA know the lyrics to hip-hop? Well, I knew the lyrics to La Boheme. All eight of us took piano lessons, and attended recitals. With my father marching around and barking orders like Captain von Trapp as my mother belted out Beethoven like Maria, I tell people my life growing up was a mash-up of The Sound of Music, The Jeffersons, and Saturday Night Live.”

In answer to my question “How did your musical background and personal love of music influence your leadership style?”—Tony said: “It’s about working together as an ensemble. A great conductor can make a high school band sound like a great orchestra. A bad conductor can make a great orchestra sound like a high school band. The conductor can bring out a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts.”

6. Choose the authentic over the artificial, every time.

Tony wished to amend a prior comment of his: “When I said we lacked for nothing, that wasn’t true. We never went to Disneyland, though it was just up the road. My dad would really lose it whenever we begged him to take us, saying—more like growling like he might’ve to his troops during Boot Camp or something—‘You don’t have any idea what the real world is like! It’s not like some make-believe ride! That’s a waste of time and money! I’ll show you what life is really like!’ Then he’d take us to the beach, or up into the Sierras, to Mount Wilson’s massive new telescope, where Hubble showed Einstein he’d been wrong about one of his big theories, or to Dad’s cabin in the desert, where he’d take us hiking. This was rustic and real, mind you, with rattlesnakes and cacti, not some air-conditioned mansion in Palm Desert with fountains imported from Tuscany. Still to this day, I often recall seeing for the first time the big breakers at Santa Monica, their power, and thinking: Dad’s right! This stuff in nature really is cool and awesome!”

7. You can only set sail if you know what your ship can do; your ship is your people.

Tony isn’t one to name names or talk out of school. But he’s quick to identify what he feels is one of the key leadership traits lacking “in all sectors of society, probably especially in politics. So many of today’s leaders don’t know what they’re doing, because they’ve not done anything, other than attend law school, maybe clerk for some judge somewhere, work as some campaign staffer or activist, and then run for office. The reason they chose Chuck Yeager to fly that risky experimental plane that broke the Sound Barrier was he was a mechanic, so he knew what his plane could do, and what it couldn’t do. He knew what a good engine’s thrust sounded like and what a problematic propellor sounded like. There aren’t any Chuck Yeagers in government these days, or at least very few of them. There aren’t any mechanics or operators, just a lot of lawyers and managers. This means our leaders don’t have the courage that comes from having taken your ship as far as it can go, because you know how it’s built. These days your ship is your people.”

Tony’s big family also helped him to learn to work with people. “My brothers and sisters and I had the same adoptive parents, so the Williams family was a heterogenous lot. This helped me to be tolerant and learn to make the most of the hand you’re dealt, to accept people on their own terms, and play the cards you’re dealt. My hand included seven adopted siblings. Some of them and I couldn’t’ve been more different. Leadership is working with the cards you’ve been dealt, including the people you’ve inherited. In extremis, you might have to do some major housecleaning, but that can’t be your go to.”

8. Diversity is much more than skin color.

When I asked him if he’d experienced much bigotry growing up in LA during the 1950s, he said, “No. I didn’t know I was different. There were all sorts in my neighborhood, and in high school. In fact, I was often picked to be in leadership positions. Same as Yale, where I was the first African-American to head my fraternity.

“Is systemic racism real? Absolutely. But there are also a lot of good people out there with a lot lighter skin than mine. Many other things are more significant differentiators than skin pigmentation. Wasn’t this King’s message?”

9. By helping others, you end up helping yourself.

My father having been a Tuskegee Airman, my husband being a pilot, and Tony having graduated from the Air Force Academy got us to talking a lot about aviation. He got the ball rolling by saying, “I’d always loved planes, and the idea of flying. I loved nothing better than when my dad took me to LA airport and we’d watch the planes come and go, roaring in and out. These were big, throaty aircraft, most of them propellor-driven, that violently pushed the air around. There were no barriers back then, no wind-breaks, and it was awesome! That led me to want to attend the Air Force Academy, but my grades weren’t good enough. Though I eventually got in, the Vietnam War got in the way of my notion of right and proper service. It didn’t seem like all those bombs and napalm being dropped on, mostly, innocents by our Air Force was right, in any sense of the word. So, I applied for Conscientious Objector status, was given an Honorable Discharge, and pivoted to helping blind vets and their children. It was my having volunteered to serve, and of being an Air Force officer, that lent credence to my volunteer work. I came from a place these poor, hurting souls could appreciate. We both understood the ship, so to speak. This was extremely eye-opening and fulfilling for me, and it led directly to my attending Harvard, to get my law degree, and then master’s in government, so I could not just serve in a reactive way, but get out ahead of these sorts of things, to avert more destructive mistakes.”

What’s Next?

Noting that Tony completed his second term as DC Mayor in 2007, I asked him “What gets you up in the morning these days, gets your motor running?”

“My final act.”

“Care to discuss it?”

“No, not yet. It’s still taking shape.”

“Well, then what are you doing on a daily basis, a concrete basis, as head of Federal City Council? I’ve read one of the things that drives you is trying to find ways to close the shocking gap between White families of historically Black D.C. having incomes that are nearly ninety times that of the average African-American family! Is this part of your final act?”

“Yes, absolutely. I want to help make D.C. the template for a modern great city. Not just one that survives, but thrives. It has the ingredients, and very unique potential. It has the ship—lots of great people, including many fine leaders. I just want to do my part.”

I have no doubt that Tony’s next act will result in another standing ovation. In my 35 years working with municipal governments, I know all too well how truly competent leadership makes the difference between only holding the line and moving forward to support everyone. Good government has to be more than entertainment and distraction. Substance, delivered with humor and humility, is what gets it done.

Colette Holt is a national expert on diversity, civil rights, public contracting and affirmative action. She serves as an expert witness, drafts legislation and policies, designs programs and manage initiatives. Her law and consulting firm, Colette Holt & Associates, is the country’s leader in conducting studies of business discrimination. Ms. Holt has served as the General Counsel to the American Contract Compliance Association for over 20 years and is an author and frequent media commentator on these issues.

Ms. Holt received her B.A. in Philosophy from Yale University and her J.D. from the University of Chicago Law School. She is a former Adjunct Professor at Loyola University School of Law and the John Marshall Law School.

Thank you for this interesting profile of a wonderful person who, as Mayor, helped Washington D.C. see its full potential.