Are Your Grand Challenge Strategies Robust?

A proven roadmap for catalyzing constructive & sustainable progress

E-book inventor Emilio Fernandez’s life journey is a case study in not only the power of principled leadership but also the wisdom of tackling monumental challenges—step by step, brick by brick. Here’s how he describes his vision behind the University of Maryland’s $67 million E.A. Fernandez IDEA Factory, which he unveiled in 2022 (at the School of Engineering that suspended him in the early 1970s after his advisor insisted Emilio didn't have what it took to be an engineer): “The grand challenges of our time are seemingly unsurmountable walls, but walls are made of blocks and we are going after some key blocks. Don’t be intimidated by the immensity of the mountain, look for and follow the hidden trails to the top.”

Indeed, a growing number of businesspeople have become interested in how they and their organizations can contribute to such efforts too. It also resonates with management scholars who are increasingly studying organizational responses to grand challenges. But how exactly can organizations identify these “key blocks” and “hidden trails” and make meaningful progress toward addressing grand challenges?

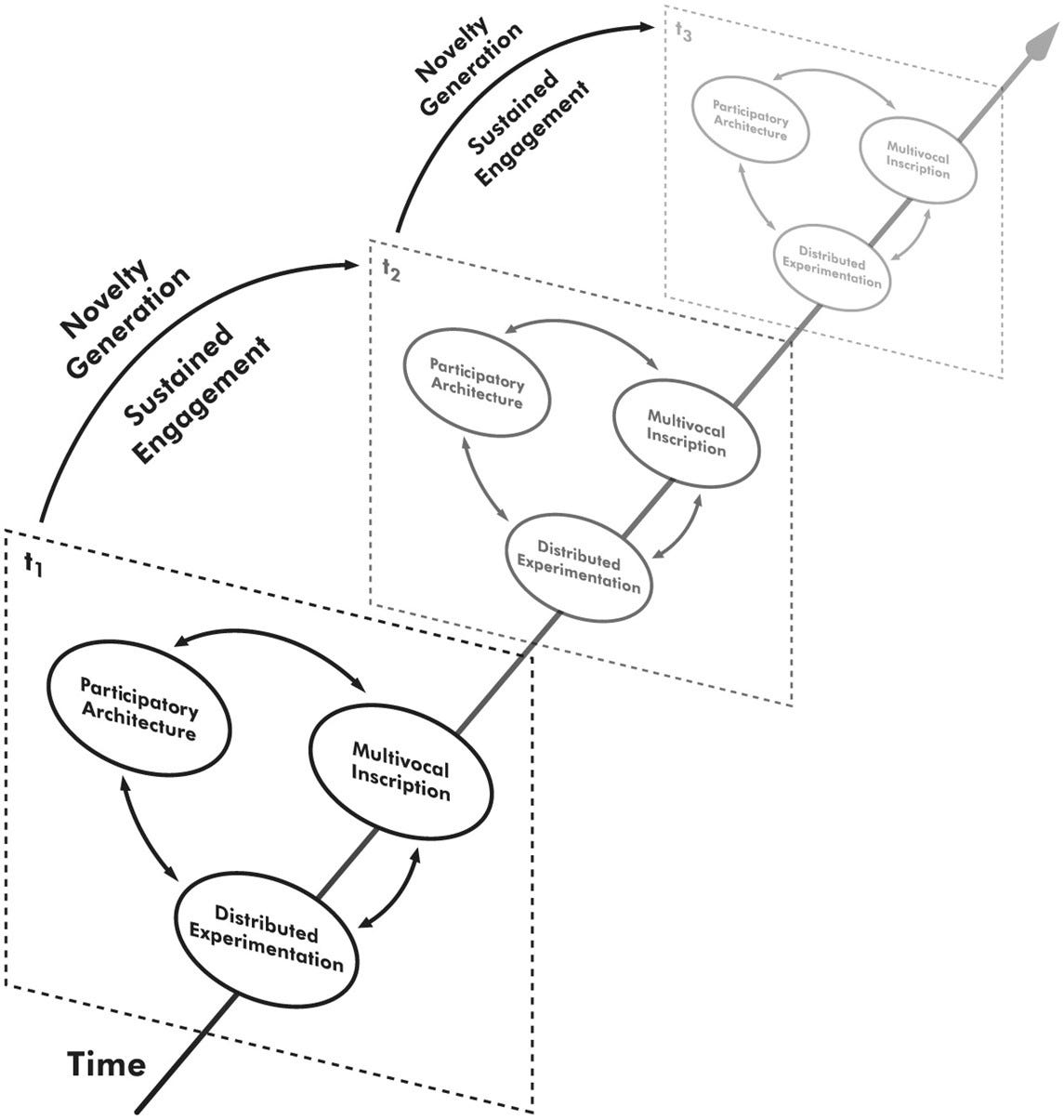

With this question in mind, Fabrizio Ferraro (IESE Business School), Dror Etzion (McGill University), and I developed a framework centered on robust action, which involves maintaining opportunities for multiple future lines of action in the face of convergence toward a particular solution. The framework provides a pragmatic approach for tackling grand challenges—matters of concern that entail complexity, evoke uncertainty, and provoke evaluativity—by focusing on three key actions: developing a participatory architecture, fostering multivocal inscription, and engaging in distributed experimentation.

Developing a Participatory Architecture

Because unilateral action cannot contribute substantially to the resolution of grand challenges, a requisite first step is to establish a participatory architecture, which we define as a structure and rules of engagement that allow diverse actors to interact constructively over prolonged timespans. Given the complex, uncertain, and evaluative nature of grand challenges, broad participation is required from scientists, local communities, consumers, and other stakeholders. The greater the complexity and interdisciplinarity of a challenge, the greater the number of concerned stakeholders. Complicating matters, evaluative criteria vary among diverse stakeholders and may well be contested. Initiating and maintaining distributed action when stakeholder priorities and worldviews are likely to be misaligned is no easy task. Initial engagement is perhaps not the difficult part—prolonged engagement is. Given the long-term horizon of grand challenges, participatory architectures emphasize the engagement of diverse stakeholders across time and space, thereby sustaining an ongoing process.

Recognizing the importance of such participatory architectures, scholars have proposed the concept of hybrid forums as a way of involving diverse actors with different evaluative criteria. These architectures create spaces where actors can meaningfully engage with counterparts, even when relations between them are publicly adversarial. The case of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), an organization that develops and maintains standards for writing organizational sustainability reports, highlights the power of participation. Even though its founders had far-reaching aspirations for promoting sustainability, they deliberately refrained from articulating them explicitly. Instead, they have focused on engaging corporations, activists, NGOs, standard-setting bodies, accounting organizations and other stakeholders. The emphasis is not on reaching consensus, but on sustaining engagement and expanding the network of participants.

Fostering Multivocal Inscription

Sustaining participants’ engagement in hybrid forums is important, but is not enough to guide action; scripts, routines, processes, norms, and guidelines must be developed. But if grand challenges are evaluative, how can these be designed in ways that will be acceptable to diverse participants? We argue that effective inscription must allow for multivocality, drawing on the idea that artifacts are interpretively flexible. In other words, meaning is not inherent to an artifact, but is constituted through interactions between actors from different domains.

The concept of “sustainable development” provides an example of multivocal inscription in the context of grand challenges. This concept was introduced in the World Commission on Environment and Development’s 1987 report, Our Common Future, which mapped out the conceptual and moral links between the environment and sustainable development goals (SDGs). The utility and success of this concept is largely attributable to different groups being able to interpret “sustainability” in very different ways. This multivocality has provoked additional engagement by providing common ground for discussion among different actors who are frequently at odds with each other. It has proven highly useful in a complex, evaluative context.

In contrast, scholars concluded that the Kyoto Protocol failed precisely because it framed the problem of climate change in a single way. More recently, the term ESG has become polarizing. Whether it will be able to overcome these challenges remains to be seen.

Engaging in Distributed Experimentation

Given their complex, uncertain, and evaluative nature, multiple solutions may effectively address grand challenges, and it is hard to know in advance how best to proceed. Under such circumstances, actors can engage in what we call distributed experimentation: iterative actions that generate small wins, promote evolutionary learning, and increase engagement, while allowing unsuccessful efforts to be abandoned.

Distributed experimentation is evident in the plethora of local efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the US. Despite a lack of a top-down national commitment to reduce GHGs, numerous state and regional policy initiatives have addressed GHG emissions from the bottom-up in what amount to a large number of distributed experiments. Local policies often are more innovative and more responsive to local environmental preferences and economic circumstances. Moreover, resource-constrained or less innovative local and state governments learn from local trailblazers and mimic successful policies. Such distributed experiments have opened up new spaces for public discussions about sustainability at the local level, and have expanded the range of stakeholders involved, thereby extending participatory architectures. Achieving beneficial local outcomes activates a positive reinforcing cycle of small wins. In other words, iteration, repetition, and continuous learning help maintain engagement and drive additional experimentation and the creation of novel institutional arrangements that actors would not have chosen ex ante.

Of course, not every experiment will prove successful, at least not in real-time. An experiment may go “wrong” by failing to deliver the expected results, or may lead to the emergence of new and previously unidentified concerns. For instance, the emergence of carbon markets has prompted various controversies regarding how these markets are organized, the calculative devices used to value carbon, and the role that markets should play vis-à-vis alternatives such as regulatory measures or technology research. But such “overflows” may be an asset, as they frequently provoke stakeholder participation and increase the multivocality of any solutions that are proposed, thereby potentially initiating another cycle of robust action.

Benefits of Using the Robust Action Framework

One of the challenges for any organization is deciding where to start. For example, there are 17 SDGs, but if you drill down, there around 170 sub-targets nested within them. Any manager may quickly feel overwhelmed and ask: “How am I going to make a dent in all of this, even with the best of intentions and aspirations?” The robust action framework can help organizations connect to the SDGs and make a more powerful impact in at least three ways.

First, the robust action framework can be used to create a map for action, even if the territory being navigated is relatively unknown. It provides an orientation, and allows you to take stock of the circumstances, make a plan, and get going.

Second, the framework provides a vocabulary for starting an internal conversation about what you’re doing and might do as part of your sustainability journey. On one hand, that might seem like a small thing. But to the extent that you embrace Wittgenstein's idea that the limits of your language constitute the limits of your world, having a new vocabulary literally can be world-changing. It enables you to see distinctions in your environment that previously went unnoticed. You can start to think about impacts you're having for good or ill that you may not be attuned to. Previously, you may have determined priorities more or less by default, or by unintentionally backing into them. Having a framework allows you to pinpoint your commitments and evaluate whether they align with your intentions.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, the robust action framework creates a way of catalyzing action and aligning the entire management team. Organizations may engage in strategy-making for many reasons, but one of the key benefits of engaging in this kind of strategic work is to foster organizational alignment by articulating what you stand for. At the same time, one of the most important things about strategy is figuring out what to say “no” to, which can actually make a big difference in some areas.

Overall, the robust action framework provides management teams and organizations with the ability to build a roadmap, to think about where they want to contribute in a powerful way to the SDGs, what they want to say “no” to, and to revisit these choices repeatedly over time. It's not just a once and done exercise. As part of our collective sustainability journey, we may learn and build capabilities in one area, and then we might decide to go further, or we might conclude that it did not work out as well as we thought, and divert our resources elsewhere.

© 2023 Joel Gehman

Joel Gehman distills principles for today’s leaders from the latest academic research, some but not all touching upon his main research foci: “grand challenges” like climate change, and “remaking capitalism.” The author of more than 50 peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters, and more than a dozen business school teaching case studies, he is Professor of Strategic Management & Public Policy, and the Lindner-Gambal Professor of Business Ethics at The George Washington University School of Business. Joel lives in Northern Virginia.

References

Etzion, D. & Gehman, J., Ferraro, F. & Avidan, M. (2017). Unleashing sustainability transformations through robust action. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 167–178. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.06.064

Ferraro, F., Etzion, D. & Gehman, J. (2015). Tackling grand challenges pragmatically: Robust action revisited. Organization Studies, 36, 363–390. doi:10.1177/0170840614563742

Gehman, J., Etzion, D. & Ferraro, F. (2022). Robust action: Advancing a distinctive approach to grand challenges. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 79, 259-278. doi:10.1108/S0733-558X20220000079024

Park, K., Grimes, M.G. & Gehman, J. (2022). Becoming a generalized specialist: A strategic model for increasing your organizations SDG impact while minimizing externalities. G. George , M. Haas , H. Joshi , A. McGahan & P. Tracey (Eds.). Handbook on the Business of Sustainability, 439–458. doi:10.4337/9781839105340.00034

Super analysis!