The world’s greatest leaders exhibit humility, love, and a service over self philosophy.

“Bob the Blue” sure did. I coined his nickname, and I alone employed it.

No one else dared.

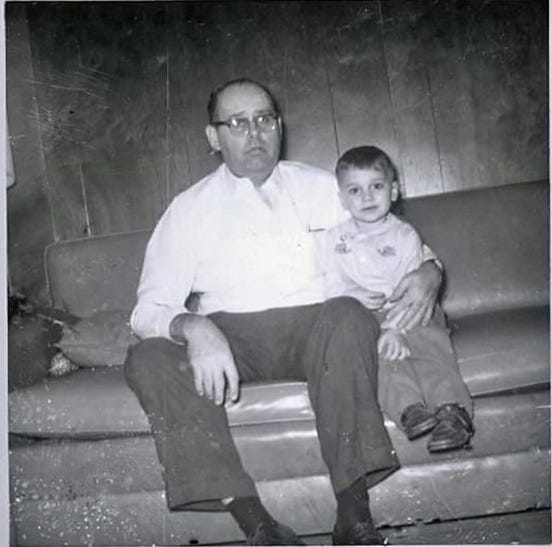

Robert W. Barker trained under General George S. Patton at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and The Desert Training Center in the Mojave Desert. After Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps defeated numerically superior U.S. and British forces at the Kasserine Pass, Patton was put in charge: he appointed Capt. Barker commanding officer of Battery A of the 65th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, and the Americans notched their first victory not just against the sly, supposedly invincible “Desert Fox,” but the Germans. It was a huge morale boost. Then Patton sent Barker to England, to prepare for the Invasion of Europe, where he got to know most of the top brass. “Dad’s favorite was General Theodore Roosevelt, Junior,” Bob’s son, Jeff, told me not long ago. On D-Day, as Roosevelt and the Ogden, Utah-born Barker approached Utah Beach aboard their landing craft, the enemy’s fearsome coastal artillery batteries locked in on them, Teddy, Jr. said “Captain Barker, let’s go up front where it is safe.” One can almost imagine the two scrumming to be the first American the Germans laid eyes on when the Higgins Boat’s gate dropped, so they could thumb their nose and say: Bring it.

The Bob I knew (from 1962 to the mid-’70s) intimidated most people. They rarely saw him smile. To them he was always “Mister Barker,” “Bishop Barker,” or “Sir,” in keeping with his status as a very influential attorney and a highly respected Elder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Most didn’t know if Bob was even capable of smiling, given the fact that, 99% of the time, his countenance was grave, his voice solemn, like that of a Wagnerian tenor.

Yet with me Bob smiled all the time. I felt privileged. Indeed I was.

Bob and I shared a lot of laughs. To me he was like a misunderstood pit bull, hoping someone would scratch his ears and invite him to join the fun. Whenever I visited the Barker home, which I did on average at least once at day between the ages of 5 and 16 as a kid growing up in Kensington, Maryland, I made it a point to invite him.

Things typically began with my hanging with my best friend, Jeff, watching Bonanza, shooting hoops in the backyard, pool in the basement, or pellet guns at empty soup cans in the cramped, shrapnel-strewn crawlspace above the pool table, across from the well-stocked, standard-issue Mormon Fallout Shelter, Emergency Medicine Chest & Food Pantry, into which, it can now be revealed, as the Statute of Limitations has expired, Jeff and I often purloined Hawaiian Punch and other LDS-kosher provisions. When we’d hear the unmistakable mechanized artillery-like sound of the garage door opening and closing, we knew—Bob was home from work.

But in truth Bob was never home from work. With the exception of a few hours sleep each night, the rare Saturday afternoon outing on horseback, and Sunday family time—which for him was sacred, Bob worked non-stop. He didn't play golf, watch sports, fish, garden, or have any earthly hobbies. His hobby was serving The Church.

Bob mostly served from his office in the iconic Octagon Building, just around the corner from The White House. He was The Church’s Man in Washington; more Robert Duval in The Godfather than lobbyist, and a force to be reckoned with. His reputation was squeaky clean. He had quite a few standing duties, like senior VP & chief legal counsel for Bonneville International Corporation (The LDS’s formidable media arm), but, because he was its best legal samurai, Salt Lake City also often tasked him with Special Assignments. Bob’s Most Special Assignment was quietly buying a strategic parcel of land in 1962 (two years before the Capital Beltway opened, three before Walt Disney bought his under-the-radar parcel in Orlando); quietly securing the zoning to perch a massive edifice atop a high promontory that would become for hundreds of thousands of drivers every day their most memorable introduction to The Nation’s Capital (and a spiritual prod to think of things more consequential than what’s for dinner or who the [former] Redskins are playing on any given Sunday); then, doggedly overseeing the efficient construction of the iconic Washington Temple.

Bob had lots of non-Church clients, too. Perhaps most important to him, he was a relentless advocate for America’s First Nations, representing more than 150 tribes in their claims against the U.S. Government. He also served as legal counsel for both Nixon Inaugurations; which led Maurice Stans to ask Bob to represent him before the Watergate Committee and in the Richard Vesco case in New York, where Stans and former U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell were co-defendants. (When Stans was acquitted, the presiding judge said he was lucky to have had such capable counsel.)

While Bob and his equally intelligent and dutiful wife, Amy, were profligate with their time on behalf of the LDS Church and its allies, to say they were financially frugal in their personal affairs is to do violence to the term. Jeff told me in 1972 that his father still hadn’t spent all the $100 he'd won for graduating #1 at Georgetown law, in 1949. “But,” as Jeff clarified recently, “Dad was not the tightest with money…that would have been Mom. Dad was actually quite generous.” And now that I think of it, that rings true. I ate more lunches at the Barkers than at my own home, and while Amy was always incredibly sweet, her Oliver Twist fare never varied: always half a cup of Campbell's soup (always tomato or chicken noodle); half a sandwich (typically tuna fish salad, never made with the "Fancy Albacore brand,” and only with celery, never the costlier sweet gherkin pickles); and between a half and a third of a raw carrot (depending on its size), typically as big around as a 100-year old oak, with dark age-rings to boot. (I guessed she got them from the stables, free; the horses refusing to eat them for fear of breaking a tooth or choking.) While Hawaiian Punch (or the much cheaper Kool-Aid) was available, as this was a special concession for guests, like a Pashtun warrior serving an adversarial Navy S.E.A.L. a cup of tea, unless Jeff was being rebellious and indulging in a luxury beverage, I joined him drinking water. Tap. Bob would no more abide Perrier or any fanciful water in his home than an SS officer singing O Tannenbaum! in The Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s Christmas Special.

So if you haven’t yet caught my drift: frugality doesn’t begin to capture the extent to which the Barkers valued and practiced thrift. Superfluity and ornamentation grated at Capt. Barker as Montgomery and cowardice grated at Gen. Patton, and his wife, though all bouncy and beaming in sharp contrast to her husband’s dour demeanor, was even thriftier.

There was one exception: horses. (Bob’s expensive suits and luxury car didn’t count: those were IRS-compliant ordinary and necessary LDS expenses, required to play the part. After all, you couldn't very much drive around Church Apostles or Nixon money men in a Corvair.) Like Patton, Bob loved horses, as did the entire family. The clearly non-materialistic Barkers owned two functional horses that they boarded at Camp Warradacca in Laytonsville, Maryland. War Admiral and Secretariat they were not. “My favorite,” Jeff told me, “was Darling.”

But apart from Bob's fondness for horses, so tight with his wallet was this rare (at the time) Mormon that many a Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, and atheist husband in my Rock Creek Hills neighborhood willingly, nay, eagerly, flipped through at least a few pages of The Book of Mormon—in the hopes that by so doing they might find buried in its challenging pages the key to unlocking the mystery of how on earth this very financially successful attorney got away with never having to buy his amazing wife a “proper wedding ring.” Amy may have been super-tight with the pursestrings, but she knew how to draw a line in the sand, too. She was self-conscious around her friends: married to IBM executives, AT&T executives, the Number Two at the FBI; they all had nice diamond rings. All she had was a modest gold band that Bob had slipped on her finger in the summer of ’42, six months before shipping off of to war.

After 25 years, Maj. Barker (ret.) finally capitulated to his sweet wife’s ironic siege, one day informing Amy: “Okay, I’ve bought you a ring but it’s hidden somewhere in the house, and you’ll have to find it.” (The neighborhood men paying close attention to this new stratagem.) That was Bob-speak for “Happy Twenty-fifth Anniversary, and thanks for doing most of the heavy lifting in raising six great kids, feeding Eric Lindner almost daily and half the heathen neighborhood kids much of the time, as well—all on Green Stamps, clipped newspaper coupons, and a few bucks a week. Oh, and The Church thanks you, too."

Bob’s aggressive thrift is one of the reasons he was tasked with the Temple mission, and why, though it’s the third-largest LDS Temple in the world, and the tallest in the world, the former tank commander brought the Alabama marble, Florence-caliber bronze, and gold leaf-coated colossus in on-time, and for less than $15 million—or about what it costs today for a Tiny Home in Napa.

When arriving at his Kensington home, at 9913 Hillridge Drive, Bob never parked on the street, or came in through the front door. He always used the garage.

As he schlepped his bulging briefcase up the unfinished concrete steps and opened the door into the kitchen, he greeted us with his stoic mask still in place. His keen but red-weary eyes still flickered, albeit barely. While I can’t say how he greeted his tribe when I wasn't there, this is how he always addressed me: “Eric the Red!”

Without fail. His words were declarative, his tone flat. He’d never say: “Eric, my boy, how are you this fine day?” Or “You—again! Don’t you have a home and a family of your own?” Though his salutation began stoically, neutrally, clinically, we all sensed the playfulness bubbling up just beneath the surface; Bob getting his second wind, awaiting his cue, like Johnny Carson awaited Ed McMahon’s.

“Bob the Blue!” I’d always respond.

Everyone within earshot would laugh and—for a few moments—all was right with the world. The Cold War, Race War, Vietnam War, and budding War of the Sexes were all of a sudden over, in one magical metaphysical omnibus peace accord.

Bob the Blue forgot about having to defend Nixon’s cronies, Amy Barker forgot about whether she’d even ask her by-the-book LDS official husband if it was okay for her to serve verboten coffee at bridge the following day to her girlfriends, as it was her time to host, and Jeff and I forgot about having to explain what we knew about the AWOL Hawaiian Punch, or why the wood for the extension to our tree-fort looked a lot like the lumber that’d gone missing from the Temple building site.

Jeff told me recently: “Dad did not smile too much (when we saw him) because he was tired. Eric, you made Dad’s day when you two exchanged banter.”

He made mine, too.

Bob the Blue’s legal skills were legendary, which meant, in essence, that he was very good at persuading people. I’ve always felt part of the reason he and I got along so well was that he sensed a tough nut to crack and persuade. (Surely more ox than fox; many people called me nuts back then and still do, but that’s beside the point.)

It was a full-court press. I met not one LDS President (aka “Apostle”) over dinner, but two. (My LDS friends are all very envious.) I played on the stake center's basketball team with the Marriotts, Mormon royalty if there’s ever been such a thing. (As well as the top Missionaries, and arguably Apostles, by virtue of The Book of Mormon being conveniently placed—not too far from the in-room mini-bar, to maintain ecumenism as well as meet their quarterly per-room earnings targets—in the 1,423,044 rooms in the more than 8,000 Marriott properties, in 131 countries.)

I listened respectfully but was never persuaded to embrace Bob the Blue's brand of faith. (My older brother converted, went on a Mission, and today spends much of his free time as a Temple volunteer.) But I wholeheartedly respected and fully embraced my humble Mormon neighbor’s work ethic, thrift, commitment to family, service to his Higher Power—and his understanding of the Greater Good.

And my respect gave way to love, the way Fortune’s pick as the world’s third greatest leader (and America’s #1 greatest) says it always does (“Alan Mulally's Engine,” Dec. 20). I loved Bob the Blue dearly, as I did and still do all the Barkers.

But one thing had perplexed me for half a century; until just recently, thanks to Alan Mulally’s insights into the motivation of servant-leaders. It’s this: why did Bob the Blue drive so recklessly?

He entered his garage like Richard Petty entered the pit—decelerating rapidly from top speed. Only instead of the King’s 1970 Plymouth Superbird, the Major drove (in its final iteration) a 1970 Lincoln Continental. What it lacked in armor-plating and ordinance, Bob the Blue compensated for with blitzkrieg speed. This exceedingly deliberate man, who walked, rode, spoke and wrote with utmost care and caution—tore down Hillridge as if in hot pursuit of the Desert Fox. That our neighborhood teemed with dogs, kids, and street football games didn't seem to faze him or be factored in any more than some Panzer tanks using a Tunisian village for cover. A human shield is a human shield, I surmised his PTSD-addled rationale must be. A Just War a Just War. Brigham Young was no Francis of Assisi.

But then it hit me. It was there all along, plain as the nose on my face and all the other actions of this supremely selfless man. He wasn’t being reckless. He was being loving. For me as a kid, Bob the Blue seemed to be driving fast, but for a guy who’d squared off against Rommel in the punishing sand dunes of North Africa, then raced amphibiously onto even more treacherous sand in Normandy—into the teeth of withering artillery, driving a luxury automobile down a leafy suburban street, even if fast, was something he could do blindfolded.

No, Bob the Blue wasn’t being reckless, negligent, inconsiderate, or anything of the sort. He was simply in a hurry. He wanted to get home to his wonderful family as quickly as possible, to spend as much time with them as possible.

I’m now ashamed I ever thought otherwise: that he could have possibly harbored anything other than the purest of motives—to be the best husband and father he knew how to be.

And boy o boy is that a terrific mission statement.

I saw a Lincoln Continental the other day, and I thought of my favorite Mormon tank commander, and how he helped teach me what it really means to be respectful and respected. And, in the words of Alan Mulally: “To love and be loved. In that order.”

Thank you, Bob the Blue, for your service!

Eric the Red

Special Thanks to Jeff Barker for refreshing my memory, correcting it, providing the photos above, editing my drafts—and making me laugh! After having been nearly inseparable for 12 years, we lost touch for nearly half a century. What a joy it's been to reconnect!

Jeff -

your Dad represents the epitome of The Greatest Generation

Brian-

Thank you!

I did not know about the guys who owned the land, and the pending shopping center!

- that your father got those three guys to reverse course is yet another example of the profound respect he commanded, by all, and his skills of persuasion!

And thank you for the dribbling basketball story...! I had forgotten some of the details...thank you for filling in the canvas!