Today I teach graduate students at Georgetown University. This is proof that no student is a lost cause.

Even though I was a year older than almost everyone else in my kindergarten class, I still barely eked out a 1 out of 5 on my first academic aptitude test. This caused my Phi Beta Kappa mother a modicum of indigestion and prompted my mild-mannered father to storm into the principal’s office and insist there must have been a mistake. “His two older bothers [one would go on to MIT, the other to Stanford] both got fives. Judas H. Priest [this was the closest my father ever got to swearing]! Why, someone from China just stepping off the boat who doesn’t speak a lick of English could get a one!”

But there was no mistake; other than, perhaps, my folks not holding me back two years before shipping me off to school, instead of one. Years later, because I failed Spanish (despite remedial summer school), I had to repeat 9th grade.

As for my future trajectory, teaching at Georgetown seemed about as likely as living on the planet Neptune.

But then I met Roger Blumenthal. Transferring schools and repeating 9th grade put me in his class at Landon School, home to the country’s finest high school lacrosse legacy. There were 51 in our class: Roger at the top, yours truly at the bottom. He took me under his wing and mentored me in how learning could be fun, fascinating, and rewarding. I started to get the hang of school.

Our 50-year friendship has been one of the greatest pleasures of my life. I’m hardly alone. He’s salt-of-the-earth: half Albert Schweitzer, half Forrest Gump. Spirits lift and days brighten whenever he just walks into a room. As the Kenneth Jay Pollin Professor of Cardiology and Professor of Medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine (the umbrella organization that governs the top-rated medical school, 16 premier facilities in the U.S., and an blue-chip global network), Roger is a highly respected teacher, researcher, and clinician. He’s also a loving and loyal son, husband, father, and friend. Anyone who knows him can attest to the fact that he’s incredibly brilliant, compassionate, conscientious, hard-working, and humble.

“What about handsome?,” he adds. “It pairs so well with humble, don’t you think?”

I respond: “I wasn’t finished.”

“Oh…”

In addition to being very handsome, in a yeshiva Doogie Howser sort of way, Roger’s Taylor Swift-like fan club knows him as someone who’s super-cautious, the antithesis of ostentatious…even though on account of the fact that so many VIP patients have become close friends over the years, you’ll often find Roger in the Owner’s Box at prestige sporting events or laughing it up with Hollywood A-listers…

“E, how much am I going to have to fork over for this puff-piece?”

He’s also really funny.

I grew up in Maryland (just across the D.C. line), between the FDA headquarters and the NIH headquarters; i.e., the global epicenter of Big Health Innovation. So I know there’s a lot of money to be made in preventing heart attacks, etc.

Making money has never motivated Roger.

Just don’t mess with his high-mileage compact car.

Not too many years ago, before upgrading to a baby Lexus so he wouldn’t embarrass his friends at Burning Tree Club in their Bentleys quite so much, he used to drive a tiny Toyota. I marveled every time I saw Roger contort his wiry six-foot-three frame into the car and behind the driver’s seat. Trust me: wherever we drove, his compact was the last car a thief would target. Yet Roger wasn’t the sort to take any chances, so before we’d pull up curbside at say one of our favorite Little Italy restaurants, he’d always take the time to carefully install The Club…a very old school anti-theft device that anyone with a hacksaw could defeat.

I’m pretty sure The Club was worth nearly as much as the Toyota.

But this same cautious mindset and meticulous attention to detail help to explain why Roger has done so much Good. So far as I can tell, no one has trained more of the world’s top preventive cardiologists, few members of the American Heart Association or American College of Cardiology are as esteemed, and few have treated as many top CEOs, government leaders, or premier athletes, coaches, and entertainers.

It’s quite possible that you have Roger to thank for your favorite QB’s winning touchdown pass or your favorite actor’s most memorable performance.

Cardiovascular disease is by far the world’s #1 killer: nearly 10 million die annually, 700,000 in the U.S. It also plays a big role in strokes and congestive heart failure. On average in any given year, heart disease claims 17 times as many lives as all of the world’s natural disasters, combined; 8 times the number from all vehicular-related accidents (cars, trucks, busses, motorcycles, bicycles, scooters, and pedestrians), 6 times as many as all of the world’s wars, and 25% more than all forms of cancer.

When I asked Roger what’s given him the greatest professional satisfaction, and what he’s most proud of, his genuine humility instinctively leads him to talk about the other superlative doctors with whom he’s collaborated at Hopkins’ Henry “Chic” Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease; including his wife, Wendy Post, M.D. As the Lou and Nancy Grasmick Professor of Cardiology & Professor of Medicine, she’s a superstar in her own right.

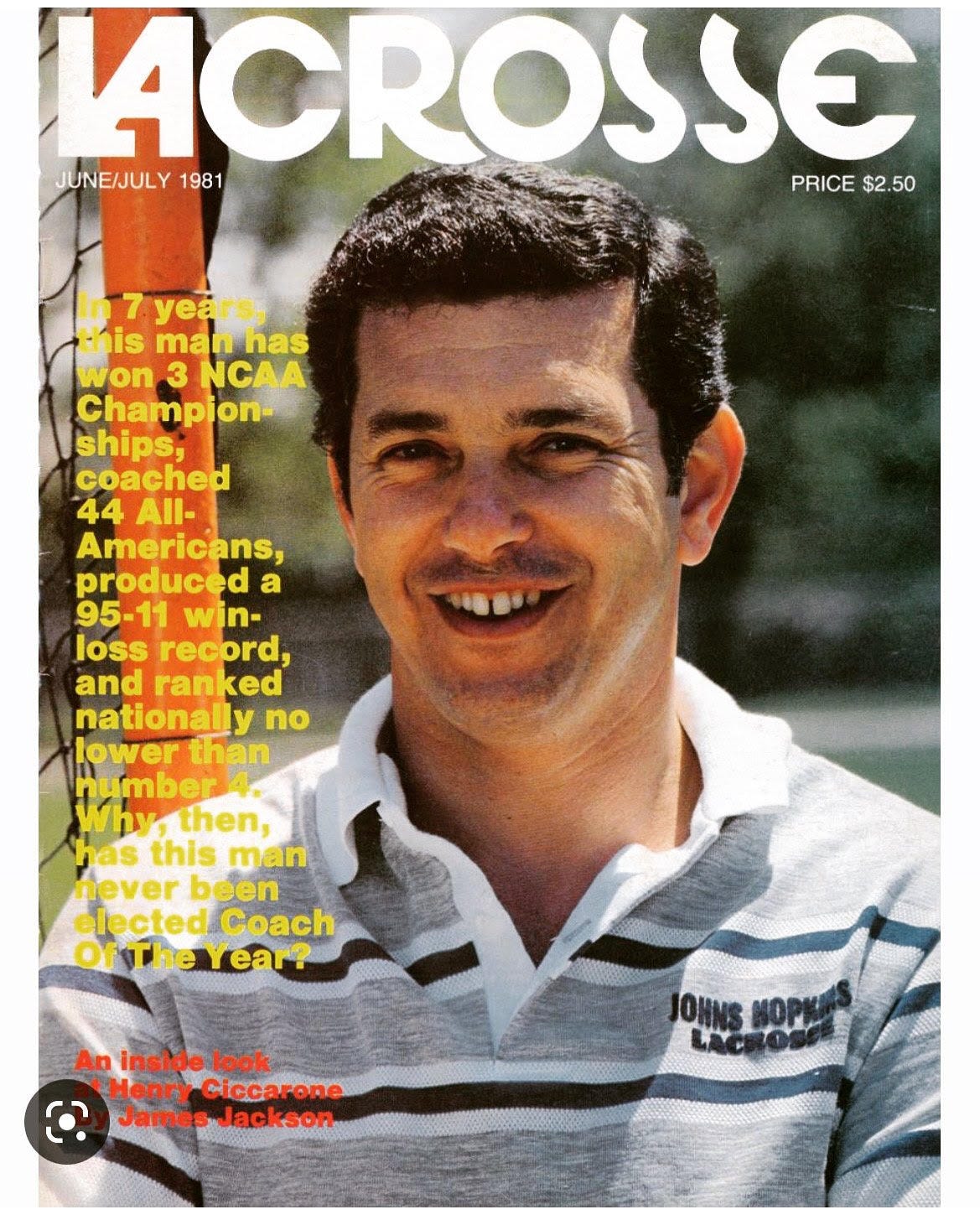

But when I pressed Roger, he held up his wrist to show me the watch he’d been given as an undergrad for serving as Assistant Sports Information Director for the Hopkins lacrosse team during the Blue Jays’ run of three consecutive national titles in 1978, 1979 and 1980 (plus a second-place finish in 1981). Chic Ciccarone was a lacrosse coaching legend: he led Hopkins into 7 straight NCAA championship games. UCLA basketball’s “Wizard of Westwood,” John Wooden, had an .808 record. Chic’s record was .862.

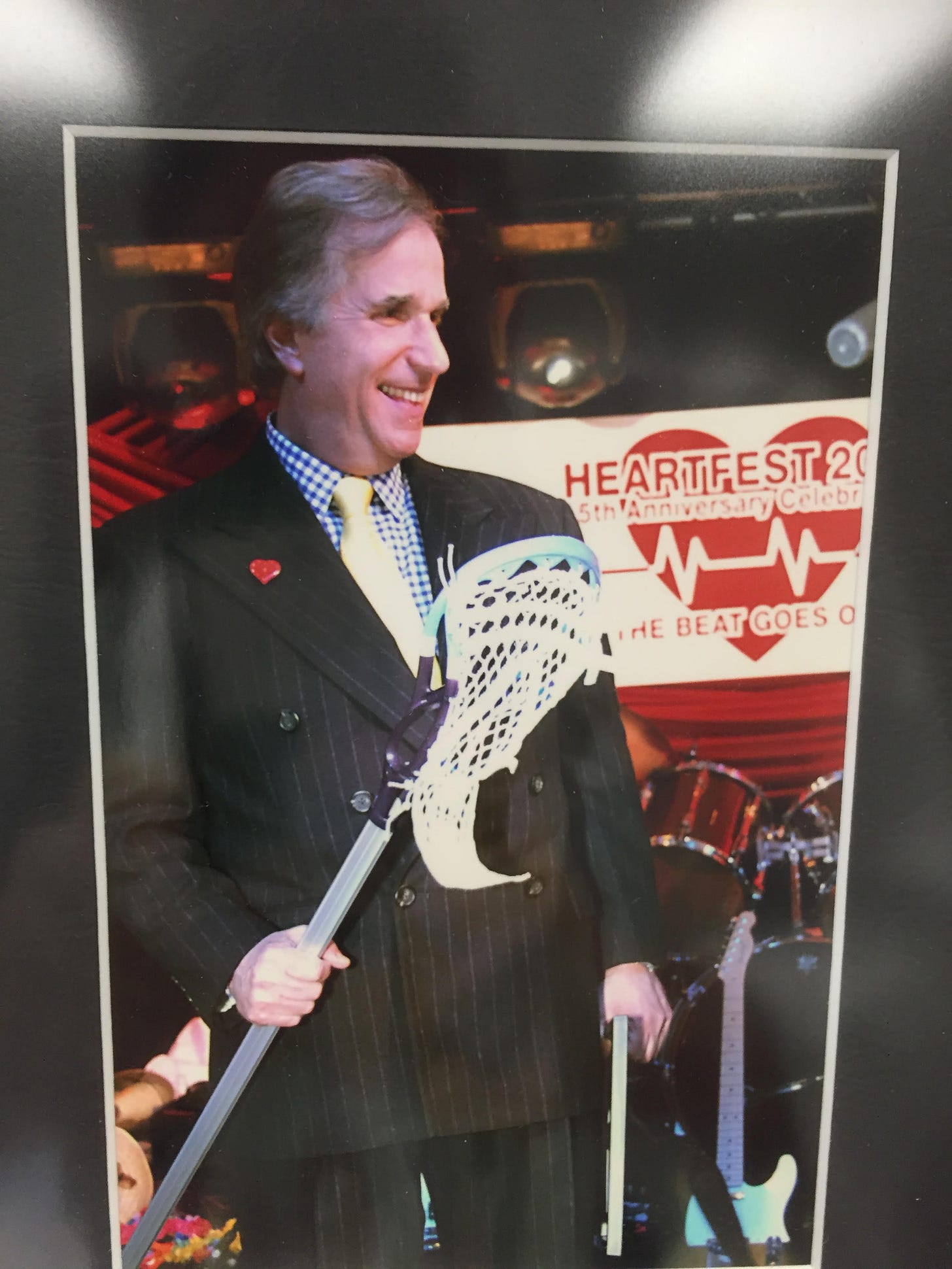

The coach and assistant sports information director became very close during the Blue Jays’ dominance. However, though otherwise super fit, Chic was sidelined by cardiovascular disease. He survived two heart attacks. Then, according to Roger, “Chic died of sudden cardiac death that was likely due to a heart attack leading to a fatal abnormal heart rhythm, also known as ventricular fibrillation.” Chic was just 50 years old. Roger was devastated.

My friend explained the watch's significance: “I get a lot of comfort from the fact that a tragedy has led to a lot of good. That the name ‘Ciccarone’ is now known more for cardiology than lacrosse.”

The late great Frances Hesselbein said that “defining moments” shape our destiny and character. Chic’s death in 1988 was arguably Roger’s most defining moment. It’s what led the young cardiology fellow to propose to Hopkins’ honchos that they give him the green light to create and run a comprehensive research and clinical Center geared to the prevention of heart attacks, strokes, heart failure, and abnormal heart rhythms, so as to save more lives and improve the quality of still more, much as the hospital had been doing in so many other fields since opening its doors in 1889.

Since the Center opened in 1990, Roger’s brainchild has directly (clinically) cared for tens of thousands of patients, and indirectly cared for millions—via procedural and pharmacological innovations, cutting-edge research, and much more. The current team of 60 faculty, staff and fellows have come from all over the world to train with Roger & his colleagues; “and teach me,” he’s quick to add.

A very short list of the Center’s many accomplishments include:

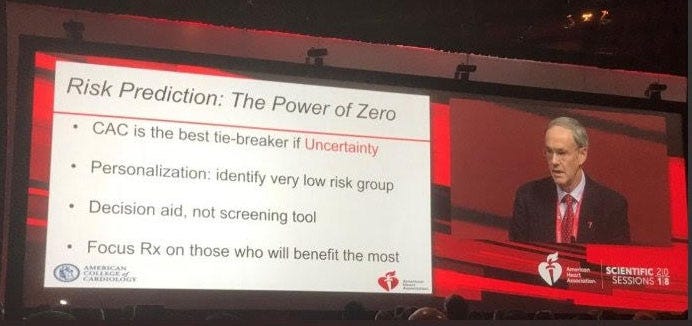

1. Pioneering improvements in the way doctors can predict the risk of a cardiovascular event;

2. Leading Digital Health Innovation efforts to improve the efficacy of risk factor profiling of those with—and without—established cardiovascular disease;

3. Conducting the leading research into and designing the best-practices protocols regarding the appropriate use of cardiac computed tomography (CT), so as to better diagnose a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease;

4. Heading the development of many American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines on cholesterol management, cardiovascular disease risk assessment, and management of chronic coronary heart disease; and

5. Establishing a renowned sports cardiology center.

When I asked Roger who—in addition to Chic—taught him what really matters in life, he zeroed in on three people: his mother, Anita; his father, Stanley (a pediatrician); and his 9th grade English teacher, Anne Sundt. (All wonderful, they also had a big effect on me.)

“What did they teach you, precisely?”

1. Don’t take your heart for granted.

“Our hearts are amazing and mystical devices. Many people first think of how this all-important organ is the seat of love, and maybe the soul, but I marvel at how it’s such a feat of engineering, at its durability in beating hundreds of thousands of times, day in, day out. Our heart doesn’t ask us for much, but it does require at least a little bit of care and maintenance.”

2. Enjoy every day—you don’t get it back.

“Both my parents stressed this. Anne Sundt did also, as you know, Eric, having us read all those novels back at Landon about carpe diem, and seizing the day. Try and enjoy every moment of every day.”

3. Don’t sweat the small stuff; so much of life is small stuff.

“Of course I’m not breaking any new ground. Lots of people have said this. Authors, life coaches. But my parents were telling me this back in the Sixties, as well as that the vast majority of things we encounter every day are small…and really insignificant, yet we humans have a tendency to obsess over this stuff; not, say, taking care of our heart. It is really important to keep our eyes on our priorities. Like family, friends, helping others—all of which are the source of true, long-lasting satisfaction.”

4. Find what motivates people, then give them the space and tools to flourish.

“Whether they’re students, staff, fellows, or plumbers fixing a leaky faucet, if you can identify what really motivates a person—this motivation is their super-power. Modest innate talent catalyzed by high motivation beats innate but unmotivated genius every day of the week.”

5. Write in short sentences. Use the active and not the passive tense whenever possible.

“Think content-rich, not fancy. Landon and Anne Sundt in particular taught me to write with economy, without resorting to frilly words.”

“You mean like eschew…”

After laughing the explosive, convulsive, endearing laugh his friends know so well, Roger said: “Like that word, yes. Some people, especially those who are highly trained, often write in a convoluted manner, for the wrong audience.”

6. Ben Franklin was right: an ounce of prevention is worth at least a pound of cure.

“There’s only so much health practitioners can do—after a life-threatening event. Once the heart muscle or cardiovascular system is damaged, managing the quantity of years and quality of life is often more challenging.”

7. The best leaders are consensus-builders.

“The pandemic reminded us that ‘medical experts’ don’t always see eye to eye. To say the least! The American College of Cardiology has more than fifty thousand members. The American Heart Association has more than thirty million volunteers and nearly three thousand employees. So it’s hardly a shock that, sometimes, the MDs, staff, and volunteers don’t agree.”

Nor is it a shock that Roger has often been brought in to hammer out a consensus. When rooms are inflated with big egos, Roger’s humility defuses the situation.

Roger’s passions for golf and preventing heart attacks speak to me on a very personal level. While I’ve never been much of a golfer, my late father was as passionate about the game as is Roger. Thirty-five years ago, my father and his three brothers were playing a round of golf together in Florida…one of the few times they’d ever done so since scattering from Syracuse. They were having a blast. My dad shared a cart with his youngest brother, Ray.

My uncle was the life of the party. Also, my father attributed much of his success to Ray’s service-over-self mentality. After my dad returned from Occupied Japan, Ray said to him: “You’re much smarter than me. You go to college. I’ll stay home, run the printing business, and look after mom and dad.” Then, as my dad struggled to pay tuition, room & board (despite the GI Bill and working several jobs), Ray sent him $20 every month. “Without those twenty dollars,” my father often said, “there’s no telling where I’d be today.”

After my dad hit his shot from the rough and walked back to the cart, on the other side of it, he found his beloved brother crumpled up on the fairway; dead, of a heart attack. Like Chic, Ray had recently turned 50.

Though my dad wept, as always, he found a way to see the bright side of things, to make lemonade out of lemons. He told us later that same day, over dinner: “That’s how Ray would’ve wanted to go.”

No question. But my father (like us all) would have much preferred Ray go to The Great Fairway in The Sky decades after he did.

Thanks to Roger—millions of people the world over are able to play more golf, throw more Super Bowl TD passes, and otherwise live much longer, more enjoyable lives.

And as for me…I’m so glad I had to repeat 9th grade!

Wonderful read! Dr. Blumenthal has made such a positive impact in his field and has saved many lives. The life long friendship between you two is extra special.